Case Studies

Scanning for a New Life in Print

How large-format scanners are driving new demand for print services.

Published

12 years agoon

Scanners, you could argue, are the Rodney Dangerfield of the modern digital print shop. When compared to the shop’s other technologies and tools, they “don’t get no respect.”

But while digital images are typically supplied by the clients these days, there are still those customers that provide you with slides, photos, or other types of original artwork that need to be digitized. And, sometimes, there are clients you wish provided you with original art – rather than delivering poor scans that necessitate a ton of Photoshop work or a return trip to the client for the artwork. Having a scanner in-house can prove to be a time-saving device, allowing you complete control over that process, including any fine-tuning you might need to do.

In addition, having in-house scanning capabilities can do more than simply fix problems. Print service providers can also tap scanners – particularly large-format scanners – as a well of service opportunities in archiving and printing. As you’ll see in the examples that follow, shops are converting old documents, murals, posters, and paintings for a new life in print, and introducing their client artists to new ways to market their originals.

But it all begins with the scanner.

An improvisational solution

Like many specialists in wide format, Awesome Graphics (awesomegraphics.com) first offered scanning services as a way to seed business for its varied output services.

“Our goal is to make it as easy as possible for our customers to order prints,” says Mike Napolitano, owner and co-founder with wife Tami of the Rutland, Vermont-based company. “Scanning their art opens up a whole bunch of opportunities for us to do printing.”

AdvertisementIn the early days of the 18-year-old company, that “art” included photographic prints, slides, and negatives. Digital photo restoration and reprinting developed as a profitable sideline for this specialist in wide format, via a LaserMaster printer.

“We’ve always offered some scanning services. I always liked the quality you could get from a 35mm slide or 4 x 5 transparency with a film scanner,” he says.

As area artists saw what the company could do with photo reprints and enlargements, they wondered if Awesome Graphics could help them, too. “A couple of local artists asked if we could reproduce their art,” recalls Napolitano. Some had slides or transparencies of their paintings, but Napolitano realized many more did not.

That seemed to limit the potential of what could be a lucrative new opportunity in fine-art reproduction. “It’s expensive to set up a photo studio for shooting paintings and artwork, and getting it right is really challenging,” he notes. “That kind of high-end work is out of the realm for most small shops.”

Unless they improvise, which is just what Napolitano did. Without the budget to invest in a super-high-end large-format scanner, he figured out how to make the scanner within his means work. Large-format scanning now helps drive the lucrative giclée fine-art printing services the company provides artists in the area and across the nation.

All our scanning is done on an Epson 10000 XL flatbed, with a tabloid-sized 12 x 17-inch scan area. “When I go right to the glass, I can capture work with the color and accuracy that can be tough to achieve with photography,” he maintains.

But it takes time and patience to digitize an oversized original. Napolitano scans the art in sections, allowing for overlap where needed. For large paintings, he builds boxes to support the work while it’s being scanned so there’s no stretch or pull in the image. Once the complete work is scanned, he loads the files into Photoshop.

“The Photomerge feature in Photoshop has certainly made my life easier,” he admits, “and I think it does a much better job than trying to manually assemble the complete image.” There’s been some trial and error to perfecting this approach: “You want to turn all color correction off in the scanner, and only adjust the color, contrast, and sharpness after you’ve finished building the composite in Photoshop,” he advises.

AdvertisementHe’s used this approach for scanning originals as large as 4 x 5 feet, for everything from fine-art originals to old Beatles posters. Scan resolution is always based on intended output. “We always scan at a very high resolution, but a scan at 2400 dpi is not always needed unless we’re scanning something very small they want to enlarge,” he notes. The company maintains an archive of all its scans, and provides clients with a CD holding a full resolution TIFF and lower-res JPEG for small prints and use on the Web.

When fine-art printing is the goal, Awesome Graphics has HP’s Z3200 12-color printer for printing on canvas or other fine-art media with archival inks. Often, though, there’s more life for the art, once scanned. On one recent project, for example, Napolitano scanned a bright painting of a lion on a 3 x 5-foot sheet of plywood for artist Melissa Alexander for reproduction as a giclée print, as well as onto T-shirts, stickers, and 9 x 10 laser prints.

“Once you have their art in your computer, you’ve got that customer,” he says. “Without these scanning services, it can be very difficult for them to re-create their work.”

Capturing maximum image data

Since it launched as a specialist in prepress and 4-color separations in 1971, American Litho Color (www.americanlithocolor.com) of Dallas has been working to help artists reproduce their work in print. The company continues that tradition today, though more often working from original art rather than film; the company’s Cruse flatbed Synchron Light scanner can digitize original art as large as 60 x 90-inches, and as thick as three inches in a single pass.

“Often artists will come to us after they’ve tried to have their work scanned somewhere else, and weren’t satisfied with the results,” says Marshall Rawlings, vice president of the family business founded by his father Arthur. “We have a controlled environment here to make sure we capture all the color of their original, even the brushstrokes.”

American Litho’s initial foray into scanning services was with film scanners to digitize slides and transparencies. As flatbed size and resolution caught up with its requirements for capturing all details and color accuracy, the company began working from original art. “We started with a Kodak scanner with a 20 x 24-inch scan area and did all kinds of work with that,” recalls Rawlings.

Advertisement“Then we heard about what Cruse had, and what it could do, we went out and bought the biggest unit they offered.” With the unit, no project is too large – the scanner has been used for everything from an 18 x 24-inch drawing to a mural measuring 5 x 15 feet. “A full-bed scan comes off this machine at one gigabyte,” he notes. “That’s about as much image information as you could want for any kind of reproduction.”

It’s the capability of the scanner to capture that much image data, along with the discerning eye for color he and his staff bring to each project, that has enabled the company to build its reputation in fine-art reproduction. “Color management is still the toughest part of this work,” Rawlings admits. “It’s a lot of work to keep all the equipment and scanners calibrated, to understand how what you see on the screen might appear when it comes off the printer.”

The company’s success has been in delivering perfect prints, without compromise. “We might proof something three to five times before we’re satisfied the color is right,” he points out. “Some artists insist on a dead-on match with their original, while some aren’t as critical. What we’re selling is an accurate reproduction of their original, and our ability to achieve that.”

American Litho has several HP and Epson wide-format printers for fine-art printing, and swaps between them, depending on the required size of the reprint. “Most of our work is done on one of our Epson Stylus Pro 9800 printers,” he says. “Anything over 44-inches is usually printed on an HP 5000.” Some artists want a digitized record of their work they’ve sold, others to resell their work through as a limited series of digital prints.

“This gives them a way to sell the same work over and over,” notes Rawlings. “When we scan a picture in our 3D texture mode, it’s hard to tell the difference between the original and our fine-art print, even if you’re holding them side-by-side.”

The combination – super-large format flatbed scanning combined with large format fine art printing – opens up new markets for the company and its clients. “We’re now working with artists from all over the world,” he reports.

A scan for every plan

When building contractors, subcontractors, and construction engineers in the upper Midwest want to review plans or drawings, or see what’s out for bid, they can log onto the Online Planning Room, a service available to members of the Minneapolis Builders Exchange (www.mbex.org). The non-profit association assists members of the construction industry with news and information on construction projects. At the site, they’ll find complete plans, architectural renderings, and blueprints for all types of current and upcoming projects in the organization’s service area of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, and North and South Dakota. “We’ve got plans for all types of commercial and state construction projects –highways, schools, and every type of commercial building,” says Christopher Geiser, technical specialist.

On average, the organization processes documents for between 3000 and 15,000 projects a year. Geiser estimates 20,000 projects have been posted to the Online Planning Room since its launch about seven years ago.

As part of his varied responsibilities, he oversees conversion of paper plans and drawings for distribution in the Online Planning Room. Everything is digitized using an Océ CS-4342S large-format color flatbed/sheetfed scanner. The CS-4342S can handle originals up to 44-inches wide. “We spent a lot of time trying to find a scanner that could pick up the level of detail, the lines, and shading you’ll find in a blueprint,” he says.

The most common size for the original documents is either 24 x 36 or 30 x 42-inches. Each is manually fed or loaded onto the scanner by him or an assistant. “We try to keep the scans at 300 dpi, but can go as high as 600 dpi if we need to,” he says. If there are any issues, the page is scanned in the preview mode, and adjustments made with built-in software. “When the image comes out, it’s good to go.”

A typical project requires scanning anywhere from 50 to 100 sheets, he says. “On special projects like the Minnesota Twins stadium built a few years ago, there were between 600 and 700 sheets,” Geiser reports. Once the scans are complete, they’re assembled and published as a project to the interactive website.

There, members can log into their account, check on the latest projects out of bid, review all plans, download scan sets or individual files, or order prints. “We probably end up printing 30 percent of what we scan,” says Geiser. “It’s always at full-size of the original sheet. With all blueprints, our members want them at full scale.”

Printing is handled in house with another Océ product, the wide-format ColorWave 600. The roll-fed color toner printer handles media up to 42-inches wide. The printer is also used to print copies of plans requested by visitors to the physical Planning Room at the organization’s headquarters. Long term, the trend is definitely to access plans online.

“More and more, people want to see those plans in a digital form,” Geiser concludes. “We’re the source, whatever they need to know about a project, from beginning to end,” he says.

A shifting emphasis to color

“In the past, our business was what you’d expect from the typical reprographics house: a lot of work in black and white, a lot of blueprint reproduction,” says Don Bitterman, president of Precision Images (www.precisionimages.com) in Portland, Oregon.

“But with the economy down the way it’s been the past few years, we’ve had to shift emphasis to where most of the business is today and that’s in color.”

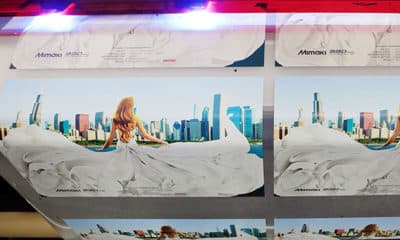

Large-format color figures in that strategy. Growth there has been helped by the large-format Graphtec CS-610 color scanner purchased a little more than two years ago. The unit handles originals up to 42-inches wide and 0.8-inches thick. For larger work, multiple scans are captured then assembled with Graphtec software.

It has proven a powerful engine for driving business to the company’s wide-format printers, says Bitterman. The shop’s printer lineup includes the Hewlett Packard Z61000 60-inch inkjet, the HP Latex 2500 printer, and Canon’s imageProGraf iPF8300. “The Z6100 is our workhorse, while the 2500 is great for outputting banners,” says Bitterman. “The Canon gives us 12-colors for the real high-end work.”

Much wide-format printing starts at the scanner. “There is no such thing as a typical color-scanning job,” he continues. “If someone comes to us with any job, and we think we can make it work, we’ll do it.”

Precision has scanned entire artists’ portfolios, old posters, and the expected mix of original paintings and sketches. “If an artist just wants a record of their work, we’ll scan it and give them a DVD,” he continues. “For the Web, we can get by with a low-res scan. When they want to reproduce the original on print, we need to know how large. It’s really about talking to that customer and understanding their needs before you scan.”

Precision’s largest scan to date: an expansive mixed-media mural measuring 42-inches x 14 feet. The scanner effectively captured every pencil line, and brushstroke. The large-format scanner also has helped with a relatively new service for the company – vehicle wraps.

“Someone will come in with a sketch or drawing on a large piece of paper of how they think they want their vehicle wrapped,” he explains. “We’ll scan that in, then blow it up to half- or full-size of the actual vehicle, and print that out to give them a much better idea of how it will look.” If needed, the print can include a sample band of the graphics in print to demonstrate how well the final wrap matches the color of their original art.

“We’ve been doing a little bit of everything with the scanner,” sums up Bitterman.

From the archive

Before the National Building Museum (nbm.org) in Washington DC received its Colortrac large-format scanner earlier this year, it had few options when architects and researchers requested the documents or plans from its extensive archive.

“It really was difficult,” says museum technician Bailey Ball. “They either could come into the museum and look at the original documents, or we could contract with some private company to reproduce them.” That could be an expensive and time-encompassing undertaking.

Since installing the Colortrac Smart LS GX+56 scanner, however, the organization has been digitizing those documents in-house, and providing them to scholars and professionals to view on a monitor or output as large format prints. The scanner’s 56-inch width makes it a practical solution for scanning plans, drawings, or blueprints.

“Since March we’ve probably processed as many as 20 research requests through the scanner.” says Ball. “When we get those requests now, we scan the original, keep one copy of the file for our archives and send them a copy on disk. My ultimate goal is to one day digitize all the key drawings in our collection.”

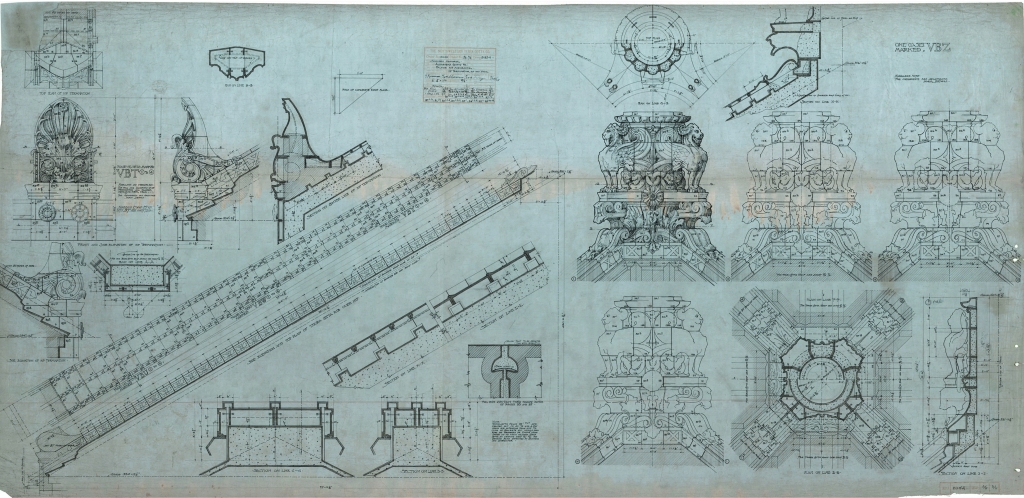

For an ink-on-linen shop drawing from 1908, for instance, Ball scanned details from a Griffin image designed by architects Palmer & Hornbostew for Pittsburgh’s Allegheny County Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall.

Another example: She’s currently in the process of digitizing portions of an archive of approximately 50,000 drawings from the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company. In its day, the Chicago-based firm (which operated from 1900 through 1954) was a leading provider of baked-form clay used to decorate commercial buildings and skyscrapers in the early 20th century. To help its clients install its products, Northwestern’s draftsmen created meticulous full-scale shop drawings to identify where and how each component fit together and should be secured to a building. The extensive collection of drawings was donated to the museum in 1982.

“The later drawings have yellowed and become quite fragile,” because of the acidity of paper then in use, says Ball, “We encase them in Mylar sleeves then process them directly through the scanner’s feeder.”

These drawings and blueprints are scanned in color at 300 dpi. “Some of the drawings use different color inks to identify certain things in the designs,” she notes. “Scanning in color really allows you to see the documents as they were intended. With the scans, it’s much easier to see fragile elements that have faded and could be missed, like pencil notes or some of the finer lines in the designs.” When touch-up or editing is required, Ball handles this in Colortrac’s SmartWorks Pro software.

On another project, Bailey scanned blueprints for some of the old S.H Kress five-and-dime stores for a graduate student studying how store lunch counters were designed to maintain the segregation of races in the pre-Civil Rights era. Ball was able to provide scans of several full-sized blueprints, as well as interior photos of the completed structures, all processed through the GX+656.

“With the scanner, we can now easily provide architectural firms and researchers whatever they need from our collection, and they can print the scans themselves at full size, if needed,” says Ball.

Scanning is just the starting point

“At one time we had two copy cameras, and we’ve had a film scanner since 1992,” says Bob Abbinanti, president of Que Imaging (www.queimaging.com) in Houston.

“We were shooting a lot of 4 x 5’s and 8 x 10 transparencies,” but thought there had to be a more efficient solution. “About 10 years ago, I looked at large-format scanners and realized they offered a way to get original art into our system in just 10 or 15 minutes,” he says.

Scanning from the original art proved to be the superior alternative. “The ability to capture the texture of the original was a big improvement for us,” Abbinanti notes. “That’s something we always struggled with when trying to properly light a painting for photography.”

The advantage arrived via a Cruse large flatbed scanner. It served Que for a decade and was only recently replaced with the new Cruse Synchron table scanner. He says the new unit delivers an improved color gamut, and handle originals up to 4 x 6-feet, and 12-inches thick.

“We can capture original art right through the glass, without removing the frame, something we never really liked doing,” he says.

An active supporter if Houston’s artistic community, Abbinanti is entrusted with scanning all types of originals, for artists and from private and public collections. The scanner’s 3D texture mode has created digitized records of Tibetan rugs and heirloom American Quilts, even granite countertops.

Often, the scanner is a starting point for a wide-format print project. “Scanning original art opens up the idea of an on-demand canvas. We’ve done a lot of fine-art printing,” he reports. “A big part of the business has been printing decorative art for hospitals. We’ll scan an artist’s original drawing or painting, then produce several copies.”

In a current project for the Houston Art Alliance, Que is digitizing a series of rare etchings from its collection, then printing them full-size as watercolor giclée prints. The originals will be stored in a safe place, while the digital reproductions go on display. On another project, the company scanned restored 16th-century oil paintings for the Catholic archdiocese, then produced fine-art prints on canvas from the files. Here again, the public will only see the digital prints made from those scans.

There’s been commercial applications for the large-format scans, as well. For redesign of a Woodland shopping center outside Houston, the company scanned a series of standard-sized paintings. These were then printed on 3M Controltac vinyl, laminated, and mounted to aluminum panels installed at the site. The largest of the images now measures 12 x 16 feet.

“Once you have a large-format flatbed scanner, and a film scanner, there’s isn’t much you can’t do,” he sums up.

SPONSORED VIDEO

Printvinyl Scored Print Media

New Printvinyl Scored wide-format print media features an easy-to-remove scored liner for creating decals, product stickers, packaging labels, and more. The precision-scored liner, with a 1.25” spacing on a 60” roll, guarantees a seamless and hassle-free removal process.

You may like

5 Current Customer Revenue Generators You Likely Aren’t Thinking About

Andretti INDYCAR Continue to Leverage HP Latex 800W for the 2024 Season

Kavalan Goes Big in United States With Media One Partnership

SUBSCRIBE

Bulletins

Get the most important news and business ideas from Big Picture magazine's news bulletin.

Most Popular

-

Blue Print4 weeks ago

Blue Print4 weeks agoThis Wide-Format Pro Started at Age 11, and 32 Years Later, Still Loves What He’s Doing

-

Buzz Session4 weeks ago

Buzz Session4 weeks agoWide-Format Printers Share Their Thoughts on Business-Advice Books

-

Columns17 hours ago

Columns17 hours ago5 Current Customer Revenue Generators You Likely Aren’t Thinking About

-

Beyond Décor: Rachel Nunziata2 weeks ago

Beyond Décor: Rachel Nunziata2 weeks ago3 Things Print Pros Must Do to Build Stronger Relationships in the Interiors Market

-

Press Releases2 months ago

Press Releases2 months agoCanon USA Unveils Enhanced PRISMA Home v1.5 Cloud Portal

-

Press Releases1 month ago

Press Releases1 month agoKornit Digital Reveals New Opportunities With Robust Showcase at FESPA Digital Print Expo 2024

-

Press Releases1 month ago

Press Releases1 month agoDrytac Set For Expansive Solutions Showcase at ISA Sign Expo 2024

-

Press Releases2 months ago

Press Releases2 months agoBrother Enters Wide Format Latex Segment With Latest Launch