On the rise of drupa 2016, the industry highly anticipated a mass coverage of inkjet solutions for packaging on the show floor. Yet it was a surprise to some – those who had been expecting more of an emphasis on folding carton packaging – to see a lot of the action centered on corrugated materials. Why the sudden interest in a new breed of printers? Will the systems currently in development fill a hole in the market? What needs are yet to be met? To answer these questions, we have to understand the “how.”

Understanding the Corrugated Market

Traditionally, corrugated packaging has been, and still largely remains, a secondary type of packaging designed for structural strength in bulk packaging of large products or batches of smaller products within the supply chain. All corrugated packages are printed, though in the past, most of the work was functional, low-coverage line-art work in one to three colors. However, in the last 20 to 25 years, about 30 percent of corrugated print has come to be printed at a range of quality levels referred to within the industry as “high color.” That encompasses line art in graduated tones up to full offset quality when laminated to corrugated board.

This demand for higher quality is being driven by two factors. First, large consumer goods and bulk quantities of those items are now sold in modern retail environments in a way that requires the structural strength of corrugated packaging. But anything that’s sold at retail has to advertise and communicate product information and brand identity – which means having offset-style quality on the packaging. Second, there’s been a strategic move – principally in the food retailing industry – to Retail Ready Packaging (RRP), which is a way of simplifying the need to re-pack bulk goods from the distributor into retail-sized quantities in separate primary packaging. If you design the secondary packaging well enough to fit physically and visually into the retail environment, it can be placed straight onto the retail shelf and become primary consumer packaging. This means print on corrugated has to rise to the standards of primary packaging. About one-third of high-color print is accounted for by the shift in retail, and two-thirds by RRP. (RRP is, at this time, considerably more advanced in Europe than in the US.)

To appreciate where and why inkjet is taking an initiative in this market, we should understand a bit about the analog competition. Inkjet can certainly have a place in corrugated, but it’s an example of a market where analog – process flexo printing in particular – is successfully responding to the challenges of increased quality and performance demands.

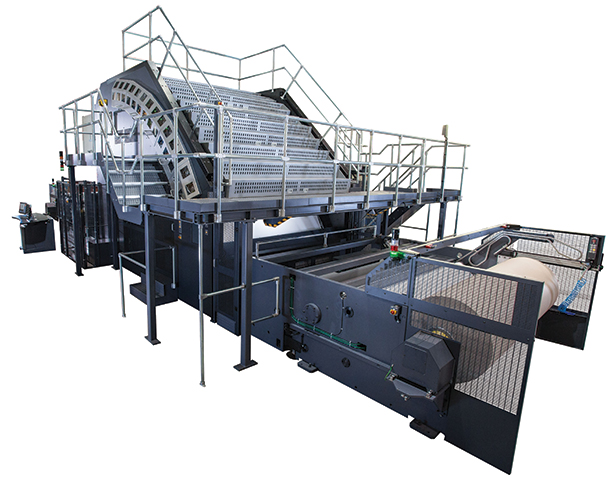

HP PageWide T1100S

Advertisement

The move to high-color print quality in corrugated predates the availability of inkjet, so solutions to the issue had to be developed within analog print. If you go back to the beginning of the RRP movement more than 20 years ago, the corrugated industry was essentially forced to break print out of integrated inline box manufacturing plants. Before that time, one- to three-color flexo line art could be printed inline with folders, gluers, scorers, and cutters at light pressures on finished corrugated constructs without damaging the 3D-laminated construct. But with the advent of high color, almost the only alternative initially was offset print, which applies a nip pressure repeatedly to substrates as an integral and necessary part of the process. The problem, however: This pressure crushed the corrugated board.

So, offset print had to take place offline, on less-vulnerable substrates that would subsequently be laminated to the finished corrugated construct. This is the origin of the term “litho [offset print] lam [lamination].” Offset print could be done on paper or on the pre-laminated top board of the corrugated construct. The print or the lamination could be done in roll or sheet format as preferred, though obviously longer runs were preferred in roll format.

Moving forward in time, packaging machinery manufacturers like Bobst and Cuir began to develop flexo machines with the ability to print at high registration to a very near-offset quality standard, directly on corrugated constructs, by employing a very light nip pressure. This was partly aided by the development of very thin, but strong, corrugated constructs known as microflutes, which were more resistant to nip pressure. This enabled inline printing in high color (effectively as good as offset for this industry, in most cases), which in turn brought the printing process back to the box makers. We call this “flexo post-print,” named for the post-sheeting/laminating process. This has been a great boon to box makers in terms of reducing cost by going from two processes back to one done inline. It has also caused a decline in the relative share of litho lam.

Inkjet for corrugated-dedicated environments arrived only two years ago. To date, it has taken two forms: roll-to-roll and sheet-fed. The roll format is available today from HP in cooperation with KBA-Kammann, and the sheet-fed format is employed by five machines at various stages of development.

Advertisement

Of the systems listed in the chart above, we would guess that fewer than 25 units are installed today at mainstream corrugated packaging sites. Within the wide-format display markets, there are thousands of UV flatbed systems, most of which at some time print corrugated board, but mostly at a lower scale for the display markets that are largely distinct from mainstream packaging.

Inkjet’s Differentiation from Analog Print

From a technical perspective, inkjet’s first point of differentiation is that it’s a non-contact print technology, meaning it can, in theory, print inline on corrugated without any of the deformation involved with offset. This is a main reason for the corrugated industry’s interest in inkjet, and, in this sense, inkjet’s selling proposition – the ability to get print back inline with conversion – is something that modern flexo can already do. The real separation comes with the second major differentiator: Digital allows real-time data to be printed with no plate changes. That means being able to print small-sized batches without stopping the press. But it can also ultimately mean printing custom, varied graphics and communications tailored in real time to the consumer trends within the universal, social media-driven dataflow. That, combined with the inline capability, is at the heart of long-term interest in inkjet.

EFI Nozomi

Inkjet’s Different Formats: Chemistry

Inkjet is being offered in two formats: aqueous inkjet and UV with a water carrier. It’s commonplace to say that water-based chemistry is preferred in packaging markets as it’s largely (and correctly) perceived to be a more neutral chemistry. The only issue is that at higher coverages over, say, 30 percent, the drying of inks with 90-percent or more water content becomes an issue of space, energy, and possible substrate deformation. That doesn’t even include the limits today on the kinds of coated substrates that can be printed, even with the use of intermediate solutions like primers and bonding agents (BA).

Durst Rho 130SPC

To combat this, some of the sheet systems vendors are offering a hybrid known as water-carrier UV inks. Such systems are very new to the market, so it remains to be seen how they will actually turn out. The theoretical advantage is that, with a water carrier, you get a flatter and better graphic image than with UV inks with 100-percent solids. A large part of its makeup is monomers – surrounding colorants – which cure transparently but in a lensed dome, causing color gamut, reflectance, and physical conversion problems. A water-based carrier allows you to get rid of a lot of those monomers and the associated problems, though of course now you have to dry water. Drying water is still a nuisance, requiring energy and space, and has potential adverse effects on the substrate. But the hope and belief is that these problems are much less severe in water-carrier UV systems than in purely aqueous systems.

Advertisement

Inkjet’s Different Formats: Roll or Sheet

Both sheet and roll systems are being offered, which illustrates the complexity of the corrugated market. Sheet systems are meant to be installed late in the manufacturing process at the box maker’s facility, usually to allow the latest-possible determination of print content in order to stay relevant. These systems allow sudden, very short runs to be produced, with content that can be varied as close to real time as possible. This is also where a great amount of analog print is done, though in analog format it’s in- or close-line printing. The extent to which digital sheet systems could be configured inline is not clear, though in early years it may not matter that much.

Roll systems seem to have two projected positions. First, a roll-to-roll system could also be placed at the end of the supply chain at the box maker – probably a larger box maker that would benefit from the higher volumes these systems allow. The box maker could bring in uncut, finished rolls of corrugation, put them through the print system, and post-cut to sheet immediately afterward in order to convert to boxes. But a roll-to-roll system could also be placed at the up-chain position of the corrugator itself.

At the corrugator level, there’s a lot of frustration because these companies have worked hard over the years to become both productive and affordable at a high speed. Printing that is done down the line in different formats (sheet or roll), using different print at varying levels of efficiency, creates a formidable tangle. This amounts to lost time and too many human interventions or costly deployment of staff. The dream of some at the back end of the industry is to bring print into ever-closer alignment with board manufacturing, using a digital information flow to coordinate content in real time with current demand and deliver pre-printed products to the converter without the converter having to do the print. Half of corrugated packaging today is supplied by fully integrated houses that both print and create the boxes themselves, allowing for a lot of additional integration of processes.

For printing to be done at the early part of the supply chain, the systems would have to be large and fast. They would also need to be versatile, not just at the highest quality print levels, but also at lower levels.

Many questions remain. Can inkjet technology, which is relatively sensitive to dust particles, even survive in a dirty corrugation plant? Can aqueous inkjet systems print fast and economically enough on coated substrates at high coverages, even at higher speeds? Are the new water-carrier UV systems economically, environmentally, and graphically acceptable to the industry? If the answers are positive – and sooner or later they probably will be – then the potential within a global market of 2.7 trillion square feet is great.

Read more from I.T. Strategies President Mark Hanley or check out more from Big Picture's April 2017 ediiton.

Best of Wide Format2 months ago

Best of Wide Format2 months ago

Columns2 months ago

Columns2 months ago

Best of Wide Format2 months ago

Best of Wide Format2 months ago

Blue Print2 weeks ago

Blue Print2 weeks ago

Best of Wide Format2 months ago

Best of Wide Format2 months ago

Best of Wide Format2 months ago

Best of Wide Format2 months ago

Best of Wide Format2 months ago

Best of Wide Format2 months ago

Best of Wide Format2 months ago

Best of Wide Format2 months ago